01

How I edit for skin tones in Lightroom

Updated for 2025! More insights! More sample photos! More about the processing… process!

Disclaimer:

There’s so much that can be said about editing.

I’ll start by emphasizing that more than anything, editing is subjective. So much in photography is. If you dig the way the skin tones in our photos look, the following post will give you some insight into my thought process and techniques (I edit all of our photos). If not, hey, glad you’re here anyhow. I often study what I don’t dig to get closer to what I do.

There really is no one right or correct way to do it. I think there are a lot of ways to do it well, and a bunch of ways to do it poorly. When you’re learning (and we’re all always learning), get a second and third and tenth opinion. Here’s just one.

Goals

I’ve got two main goals when I’m editing wedding photos (or really any photos with people):

Fit the general editing vibe I’m after

Importantly, and above all, I’ve honed an idea of what I think looks good — and I edit in a way that gets as close to that as possible. The answer to this, aka what end result would make you happy, could differ wildly from me. It takes a lot of practice, a lot of looking at your images and the images of others, to help really nail down what you’re after. Light, airy, dark, moody, film-like, true-to-life — all equally valid. Just be sure you know what you’re aiming for, or you’ll never know if you get there.

Flatter the skin tones

We’re social creatures, and our eyes & brains are hardcoded to identify and study people’s faces. We’re drawn to them, and they interest us to no end. So I make sure to put a good deal of thought (and time and intention) toward nailing the way my subjects’ skin looks. This is sounding weird haha.

Note the emphasis on flattery, not getting the “correct” skin tones. Busting out a white/gray card or color checker is great in product photos when accuracy & precision matter, and a great way to get boring and/or unflattering photos with technically-correct skin tones.

Some people hang their hat on technical correctness. I do not. I think it’s boring and lame. My images, both from my client’s and my own perspective, are better when they emphasize a flattering feel, so I lean toward that.

What does that actually look like? Let’s talk about that.

What I aim for

In the camera

So much is determined at the time you push the shutter button, so I always “shoot for the edit.” Once you’ve shot enough and edited enough, you know the quality of the images you’re shooting (or have just shot) before ever reviewing them in Lightroom. The better you’re able to identify things that are gonna be a pain during editing, and advocate in the moment to adjust and minimize them… the better.

Because editing is really only fun when you start with a photo with good light to begin with. Ask any wedding photographer how much time they’ve spent trying to “save” a photo that has terrible lighting (harsh, washed out, mixed lighting temperatures indoors, completely un-artfully missed focus) and the answer will be “too much.” We’ve all been there and it blows.

Yes it’s true that a truly incredible moment would make an incredible photo independently of the lighting conditions. But generally, a big part of making great final images is capturing good starting images in interesting, flattering, light. Work what you have in front of you, while you’re there, to minimize the time you spend salvaging images.

This could be as simple as turning your subjects a touch so the light falls evenly across their bodies (or at least faces). If you have the power to move a session to morning or evening, doing that is almost always a good call. It could be minimizing background distractions including intense light that distracts from your subjects.

This is vague advice! But that’s because the control we have over light, or even our subjects sometimes, can vary wildly. We’re always trying to make the most of what we have. I’m just stressing that good edits start long before you open Lightroom.

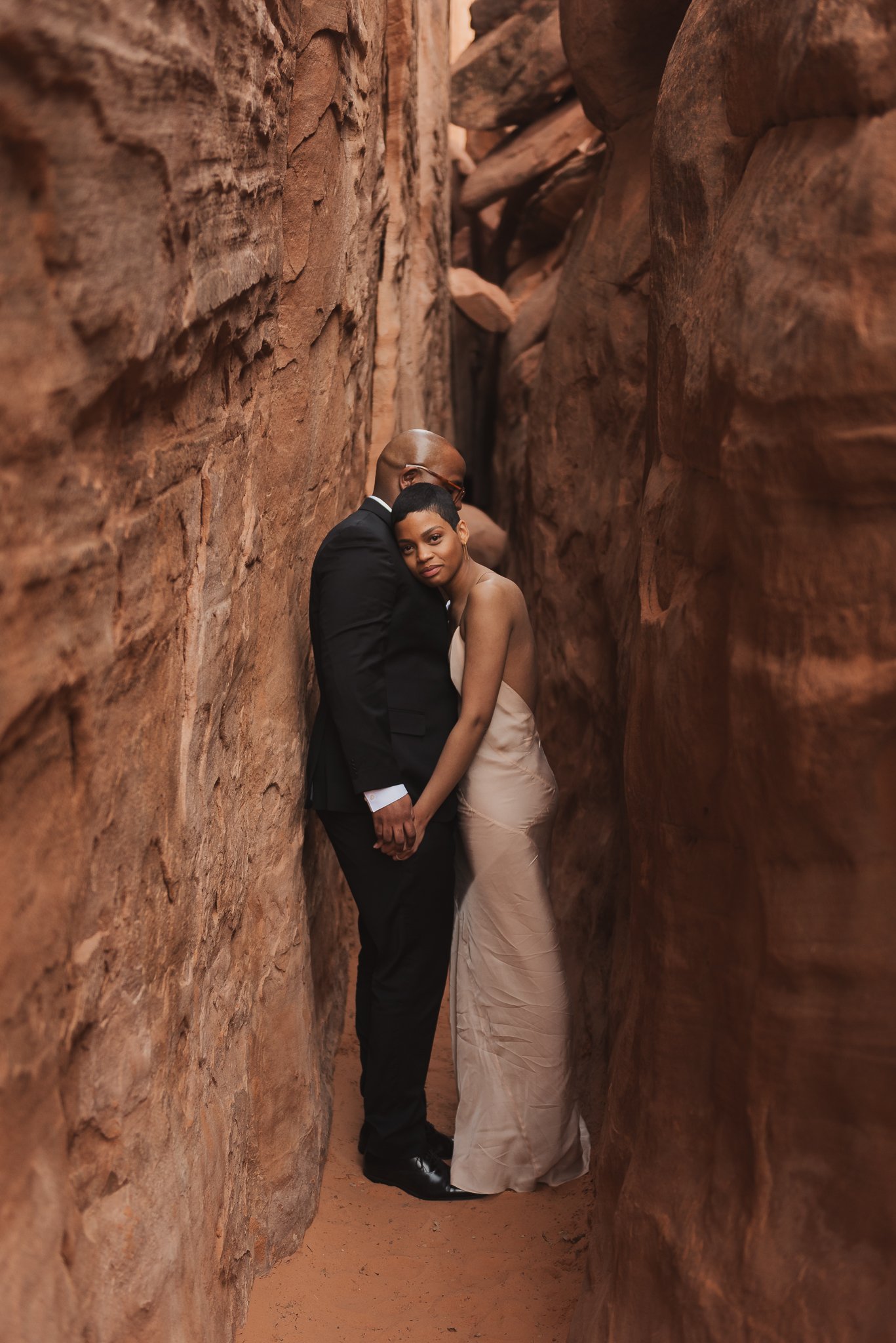

Breakdown: Might’ve seen this on our homepage! Love this shot.

Making the most of “harsh”, noon-ish light here. See how the man on the right has the top of his shoulder a lil blown out (totally fine), but both his face and his husband’s faces are (mostly) evenly lit? This is intentional positioning (and direction, and shot selection) so that the most important part of the images — their faces — are evenly, flatteringly lit.

I probably started further up the trail on the right where they’re headed, but noticed that from the perspective at least one of them would have harsh (uneven) light on too much of their face. So I move to a spot where they can walk past me.

Here the tiny amount that’s blown out (shoulders mostly) help draw the eye to my subjects.

Framing them in the opening between trees reduces distraction from the background.

For contrast

I’m looking for a flattering relationship between the lit and shaded parts of a person’s face — even in direct light (which I love). Often the issue is not the quality of light that direct, even sunlight provides, but the unflattering or uneven shadows it creates. Direct light calls for tighter control and consideration to the shadow parts.

And to the fact that the sun is bright and will make your subjects squint.

I don’t want the bright spots to be super bright/blown out, nor entirely dark. Again you might, but I’m going for something a little softer.

Technically, skin tones tend to occupy the middle tones of an image (the middle range between very bright and very dark) and I don’t like to have a lot of contrast within this range. It tends to look crunchy and harsh, especially in close-ups. I avoid using the clarity slider (at least in these parts of the image) for this reason — used globally, it adds contrast in the mid tones (the skin tones). I don’t prefer the look, but hey you might! Same is true with the texture panel. Can be fine for wider shots, but adding texture to closeups is generally not flattering (though there are specific uses of course where I think this works).

Orig, shadows boosted, crunchier (clarity + contrast)

Breakdown: Fun indoor snap (of new earrings) near a huge window

See how half of this guy’s face is in shadow? A mistake I see often is to remove most of that shadow in the quest for a more flattering shot, but all that really does is flatten the image (literally by removing the depth that creates shadows) and bringing the photo closer to the uncanny-valley. On some level most viewers know that being lit from a direction means a pronounced shadow on the opposite side. Nothing wrong with preferring this! It’s just that I don’t. Also, would you have noticed if I hadn’t mentioned it, or if there weren’t other images to compare it to?

Importantly too, the shadow isn’t super super dark and the transition between the lighted side and the shadowed side is smooth. Honestly adding clarity and contrast like in the third image doesn’t look bad — but overtime I’ve avoided dramatic/gritty look for a softer preset that’s more applicable to more lighting conditions. Again, preference! Over my career I’ve played with varying levels of “grit” and could very likely return to incorporating more of it.

Extra importantly — I’m in the photo haha.

For temperature

I’m aiming for the cool side of warm. I don’t want blueish sickly skin, and I don’t want overly orange fake golden hour — unless it was actually like that, and even then I evoke that warmth without going overboard. While I don’t follow it strictly, I do check the warmth technically using this method:

Grab the white balance dropper (W) and hover over the brightest part of someone’s upper cheek and then look at the RGB values under the histogram in the right-most panel of the edit module.

Red should be the highest number, green second highest, and blue the lowest.

Ideally the gap between the blue and green values is roughly the same as the gap between green and red. This gap should be more than 5 (to keep them from being too gray).

Taking the general vibe into account, I’ll edit WB until it’s too warm, and back it down until it feels about right. Then I’ll check the values to make sure I’m not wildly off the mark.

Blue values higher than green? Add warmth (yellow).

Gap between values not at least 5? Needs more saturation, either through the saturation slider, preferably the vibrance slider, or a result of using the contrast slider (which increases saturation). Can also so be achieved in the tone curve, but that’s beyond the scope of this article — and something I never do.

Breakdown: couple in an aspen grove!

Between the tree cover blocking light above and the yellow/green color casts introduced by the foliage, these kinds of shots can be tricky to white balance. The above method is great for keeping you on track as you fine tune your look.

Closing thought on “correct” vs flattering white balance

Just want to drop another note here on correctness — jettison the idea from your brain and your photos will probably improve (and the time you spend editing will decrease).

Do what flatters your subjects, what they’d like, and what you’d like.

As exported.

This shot was at the very end of the session, with rain starting and a storm rolling in. This is way more representational of the color tone and light levels at the time. Is it better because it’s more correct? I don’t think so. Without the context of changing light levels throughout their whole gallery, this shot looks unfinished in isolation.

Dark skin tones & presets

Worth noting that 99.9% of the time my WB adjustments are global (affect the whole image) as part of my custom preset. In rare instances I’ll do some selective WB adjustments using a brush layer, but the effect looks weird very quickly. I use it sparingly, and only when I need to clear up a color cast.

Crucial:

When you’re designing your preset (and you should absolutely use a preset in your workflow eventually), make sure you’re including a broad range of skin tones during testing. If you’re purchasing a preset, make sure that darker skin tones are represented in samples.

Still building portfolio and don’t have enough variation to test your preset on? Plenty of places on online have raw sample images from just about every lens/camera combo out there.

Dark skin tones have some extra considerations but aren’t necessarily more difficult to edit, as they follow the same rules and suggestions as light skin — look back at the RGB value method above — they’re just darker.

A note on cinema

Onto a bit of a tangent here: I love movies. I’m constantly looking to movies for inspiration on examples of color grading that I find interesting. More than once I’ve seen a film so gorgeous that my editing veers into that direction for a year or more.

Thing is, stills from a movie don’t need to stand on their own as they’re not viewed that way.

If a scene takes place at dusk for instance, it’s common to see skin tones take on the more “correct” “naturalized” blue hue, or in heavy shadow. When a photo takes place at dusk, I don’t generally let them dip as far blue; I want each image to stand on its own to a degree and be consistent with the set, and though a strong tint could make perfect sense in the film’s context, I don’t think it generally does for a still frame.

So I’ll go on the cool side of warm but seldomly cool. I’ll go on the darker side, but not super heavily-shadowed. At least for general wedding photography! In other kinds of portraiture with more flexibility or a more editorial look, I love it.

Fuck it, try B&W

Last tip: if a photo is particularly challenging to nail the skin tone (or exposure), try it in black & white.

Mixing multiple color temperatures indoors? Wicked-heavy backlight and flare? Intense green color cast from foliage? Sometimes the light is just too damn weird. What a great reason to try the photo in B&W.

If it still doesn’t work in B&W, the shot probably needs to be tossed.

-Austin